Like all nebbishy Jewish boys since 1993, all I have ever wanted is to be Ian Malcolm.

And so, it brings me great pleasure to offer the following paraphrased thesis: I have spent so much time wondering what makes a great latke, I never stopped to consider: what makes a latke?

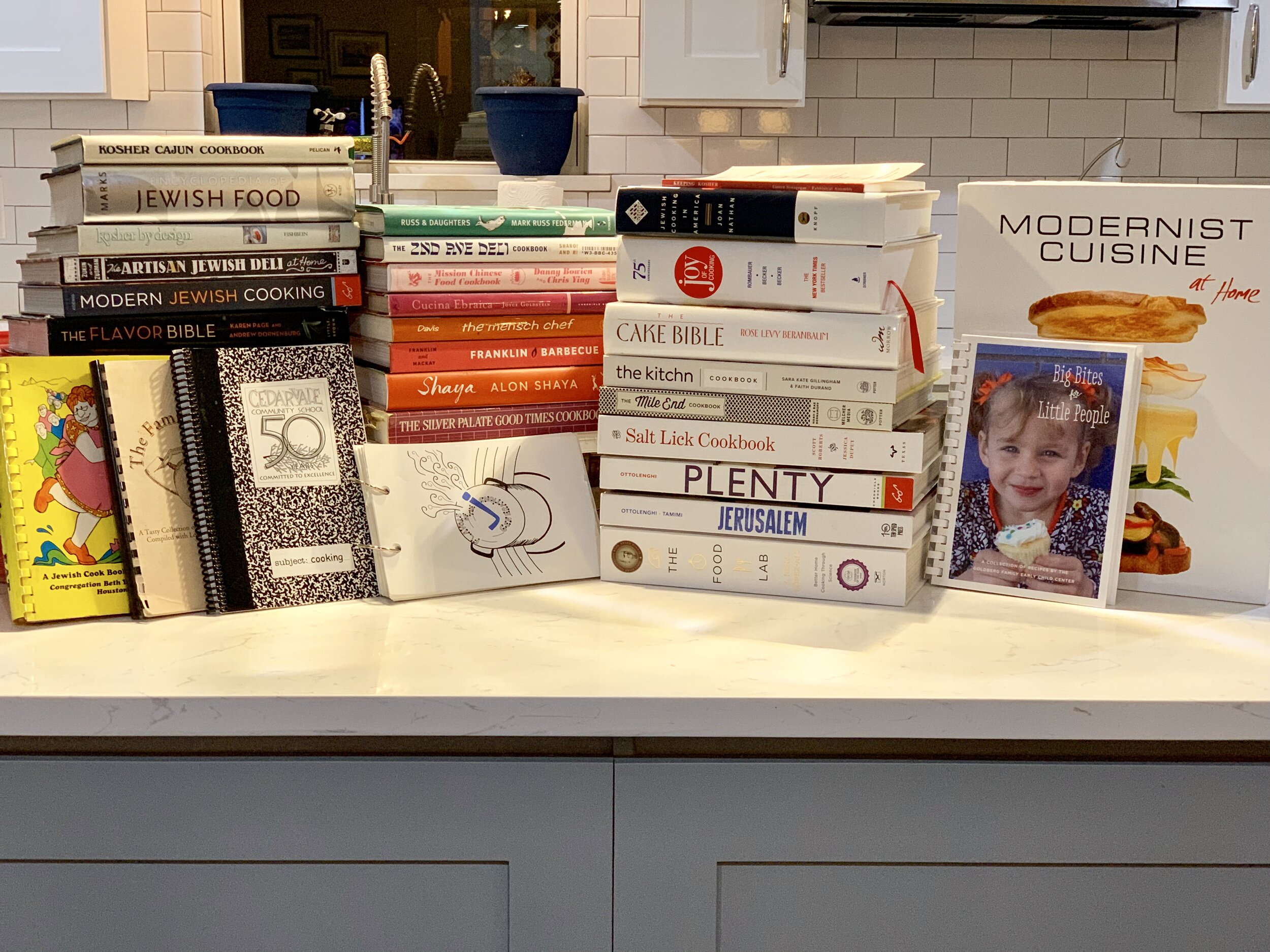

So I turned to the one true repository of this sort of knowledge: The Encyclopedia of Jewish Food by Gil Marks, a truly gargantuan tome which has a fantastically researched entry on just about every Jewish food you can think of and about 300 you've never heard of.

Of course, we are taught that latkes celebrate the oil from the miracle of the menorah - latke is Yiddish for "little oily pancake" and even more appropriately seems to descend from the Greek word for olive oil. That doesn't necessitate the potato or root vegetable shreds that have become ubiquitous to their construction. So what's the deal?

As with most good things in Ashkenazic Jewish cuisine, fried pancakes first appeared on the Italian Jewish scene before moving north (#sorrynotsorry). In the late 1200s, my new hero Rabbi Kalonymus ben Kalonymus included pancakes fried in oil as an ideal food to serve at both Purim and Hanukkah. When the Inquisition expelled the Jews from Sicily in the late 1400s, they brought the pancakes they had been making, which included ricotta cheese, to northern Jewry, and they became the norm.

The further north the recipe traveled, however, they ran into a few problems: during the winter months (aka Hannukah time) in northern Europe, cheese and butter become luxury items. Further, the olive oil used to fry the ricotta pancakes was not in nearly the same wide supply, and the common cooking fat, schmaltz, would not work with a dairy dish. So substitutions needed to be found.

The first attempts were rye, buckwheat pancakes that ended up morphing into blintzes and crepe variations over time. Potatoes, which can be grown in poor conditions, grow in abundance in a short cycle, and can be stored through the winter - were seen as a poor-person alternative. It wasn't until the late 1800s, due to a number of crop failures and economic depressions, that the potato latke gained widespread acceptance.

I cannot recommend The Encyclopedia of Jewish Food highly enough; I have never read a section that did not give me new and fascinating insight into Jewish cuisine. And so I set out to make the latke of our forefathers.

Ashkenazic Cheese Pancakes, from the Encyclopedia of Jewish Food

Ingredients

2 cups (16 oz) drained ricotta cheese

4 large eggs

¾ cup all-purpose flour

2 Tbsp. sugar

½ tsp. vanilla extract

1 tsp. kosher salt

Oil for frying

Instructions

In a large bowl, whisk together all ingredients.

Heat a thin layer of oil (no more than 1/8th of an inch) in a large skillet or griddle over medium heat.

In batches, drop heaping tablespoons of batter into the skillet and fry until top is set and the bottom is lightly browned, about 3 minutes.

Turn and fry until golden, approximately 2 more minutes.

Serve immediately.

The Review

Belly Score: 8/10

Lokshen Kugel in pancake form, which is not something I realized I needed in my life until they were melting in my mouth. Soft, pillowy, full of flavor. The best bits are the crispy caramelized edges of the pancake that offer a perfect crunchy counterpoint to the softness of the cheesy center. That said, if someone said they were making me latkes and handed me these, I might be a bit confused. Does the central DNA of being a fried pancake hold enough identification to carry such a wide range of food items under a singular banner? A more rabbinical blogger than me might suggest that the variance offers a poignant metaphor of the wide-ranging experience of Jews in the world and our need to accept all comers. I will simply enjoy these contentedly and see what Mrs. Belly has to say.

Mrs. Belly Score: 8/10

”Really good. Not a latke.”

Well then.

Baby Belly: N/A

Giggled as he ripped his apart and threw them to our dog (The Canine Belly). Only agreed to eat bananas and Cheerios. Giggled some more.